Designing A Food Forest: The Seven-Layer Forest Garden

Get ready to create your own seven-layer forest garden!

Food forests, or edible forest gardens, are life-filled places that provide habitat for wildlife and food for humans while promoting natural beauty and biodiversity. To get started, all you need is to take a page from Mother Nature’s book.

The following is an excerpt from Gaia’s Garden by Toby Hemenway. It has been adapted for the Web.

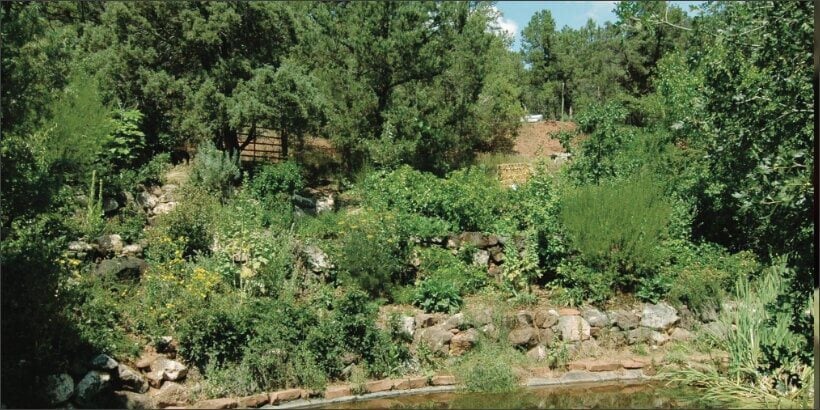

All illustrations by Elayne Sears unless otherwise noted. Featured image by Jerome Osentowski.

Food Forest: The Seven-Layer Garden

It’s time to look at forest garden design. A simple forest garden contains three layers: trees, shrubs, and ground plants. But for those who like to take advantage of every planting opportunity, a deluxe forest garden can contain as many as seven tiers of vegetation.

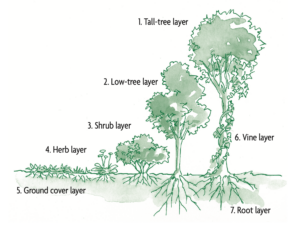

As the illustration below shows, a seven-layered forest garden contains tall trees, low trees, shrubs, herbs, ground covers, vines, and root crops.

Here are these layers in more detail.

The seven layers of the forest garden.

The Tall-Tree Layer

This is an overstory of full-sized fruit, nut, or other useful trees, with spaces between to let plenty of light reach the lower layers.

Dense, spreading species—the classic shade trees such as maple, sycamore, and beech—don’t work well in the forest garden because they cast deep shadows over a large area.

Better choices are multifunctional fruit and nut trees.

Fruit & Nut Trees

These include standard and semistandard apple and pear trees, European plums on standard rootstocks such as Myrobalan, and full-sized cherries.

Chestnut trees, though quite large, work well, especially if pruned to an open, light-allowing shape.

Chinese chestnuts, generally not as large as American types, are good candidates. Walnut trees, especially the naturally open, spreading varieties such as heartnut and buartnut, are excellent. Don’t overlook the nut-bearing stone piñon and Korean nut pines.

Nitrogen-Fixing Trees

Nitrogen-fixing trees will help build soil, and most bear blossoms that attract insects. These include black locust, mesquite, alder, and, in low-frost climates, acacia, algoroba, tagasaste, and carob.

Since much of the forest garden lies in landscape zones 1 and 2, timber trees aren’t appropriate—tree felling in close quarters would be too destructive.

But pruning and storm damage will generate firewood and small wood for crafts.The canopy trees will define the major patterns of the forest garden, so they must be chosen carefully. Plant them with careful regard to their mature size so enough light will fall between them to support other plants.

The Low-Tree Layer

Here are many of the same fruits and nuts as in the canopy, but on dwarf and semidwarf rootstocks to keep them low growing.

Plus, we can plant naturally small trees such as apricot, peach, nectarine, almond, medlar, and mulberry. Here also are shade-tolerant fruit trees such as persimmon and pawpaw. In a smaller forest garden, these small trees may serve as the canopy.

They can easily be pruned into an open form, which will allow light to reach the other species beneath them.

Other low-growing trees include flowering species, such as dogwood and mountain ash, and some nitrogen fixers, including golden-chain tree, silk tree, and mountain mahogany. Both large and small nitrogen-fixing trees grow quickly and can be pruned heavily to generate plenty of mulch and compost.

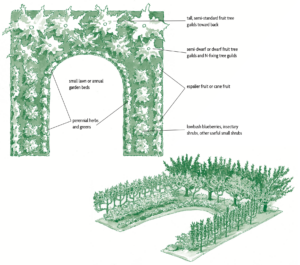

A forest garden for a rectangular yard. Large trees are placed far apart so that light can reach shrubs and smaller trees. Vegetable or flower beds are located on the sunward side.

The Shrub Layer

This tier includes flowering, fruiting, wildlife-attracting, and other useful shrubs.

A small sampling: blueberry, rose, hazelnut, butterfly bush, bamboo, serviceberry, the nitrogen-fixing Elaeagnus species and Siberian pea shrub, and dozens of others.

A Broad Palette

The broad palette of available shrubs allows the gardener’s inclinations to surface, as shrubs can be chosen to emphasize food, crafts, ornamentals, birds, insects, native plants, exotics, or just raw biodiversity.

Shrubs come in all sizes, from dwarf blueberries to nearly tree-sized hazelnuts, and thus can be plugged into edges, openings, and niches of many forms. Shade-tolerant varieties can lurk beneath the trees, sun-loving types in the sunny spaces between.

The Herb Layer

Here herb is used in the broad botanical sense to mean nonwoody vegetation: vegetables, flowers, culinary herbs, and cover crops, as well as mulch producers and other soil-building plants. Emphasis is on perennials, but we won’t rule out choice annuals and self-seeding species.

Again, shade-lovers can peek out from beneath taller plants, while sun-worshiping species need the open spaces. At the edges, a forest garden can also hold more traditional garden beds of plants dependent on full sun.

The Ground-Cover Layer

These are low, ground-hugging plants—preferably varieties that offer food or habitat—that snuggle into edges and the spaces between shrubs and herbs.

Sample species include strawberries, nasturtium, clover, creeping thyme, ajuga, and the many prostrate varieties of flowers such as phlox and verbena. They play a critical role in weed prevention, occupying ground that would otherwise succumb to invaders.

A U-shaped forest garden. If the U opens toward the sun, the garden also forms a sun-trap. A symmetrical planting arrangement gives a more formal appearance, less symmetry makes the garden feel wilder.

The Vine Layer

This layer is for climbing plants that will twine up trunks and branches, filling the unused regions of the all-important third dimension with food and habitat.

Here are food plants, such as kiwifruit, grapes, hops, passionflower, and vining berries; and those for wildlife, such as honeysuckle and trumpet-flower.

These can include climbing annuals such as squash, cucumbers, and melons.

Some of the perennial vines can be invasive or strangling; hence, they should be used sparingly and cautiously.

The Root Layer

The soil gives us yet another layer for the forest garden; the third dimension goes both up and down.

Most of the plants for the root layer should be shallow rooted, such as garlic and onions, or easy-to-dig types such as potatoes and Jerusalem artichokes.

Deep-rooted varieties such as carrots don’t work well because the digging they require will disturb other plants.

I do sprinkle a few seeds of daikon (Asian radish) in open spots because the long roots can often be pulled with one mighty tug rather than dug; and, if I don’t harvest them, the blossoms attract beneficial bugs and the fat roots add humus as they rot.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

“An immediate halt to chemical fertilizing and returning to the use of compost instead would turn degeneration into regeneration.”

Read MoreIf you’re not familiar with silvopasture, you should be. The integrated system offers both the promise of land regeneration and economic livelihood.

Read MoreAs the weather heats up, now’s the perfect time to grow and pick cucumbers! With these easy tips and tricks, you’ll be prepared to successfully harvest and store the cucumbers you grow until they’re ready to eat. Unless otherwise noted, all photographs copyright © 2017 by Andrew Mefferd. The following is an excerpt from The Greenhouse and…

Read MoreSome of the world’s most productive and resilient soils contain significant quantities of “natural” biochar. Author Kelpie Wilson challenges us to “change our perspective from ‘too much carbon in the air’ to ‘not enough carbon in the soil.’ We are good at being miners and exploiting resources, so let’s mine the air and stash the…

Read MoreAside from the sheer pleasure of telling your friends, straight-faced, that you maintain your garden using something called a “chicken tractor,” there are a slew of other benefits to working the land with a few of your animal friends. Getting rid of pests without chemicals, for one; letting them do the work of weeding and…

Read More