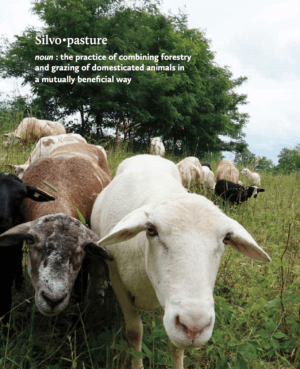

The Art of Grazing: What Is “Good” Silvopasture Grazing?

If you’re not familiar with silvopasture, you should be. The integrated system, which combines aspects of forestry, animal husbandry, grazing, and ecology, offers both the promise of land regeneration and economic livelihood. In order to succeed you need to understand a key component of the system: the art of grazing.

While it may seem like a simple concept, grazing – or perhaps better said, overgrazing – can be detrimental to your silvopasture strategy. But with a little planning, time-management, and the ability to expect the unexpected you can effectively realize Steve Gabriel’s vision of “an ecosystems approach to farming, where many goals can be achieved side-by-side, in scenarios that are win-win-win for each of the components… And, with good planning, we can see profit from the farm.”

The following excerpt is from Silvopasture: A Guide to Managing Grazing Animals, Forage Crops, and Trees in a Temperate Farm Ecosystem by Steve Gabriel. It has been adapted for the web.

While it can be argued that across the board animals will benefit from trees in the areas they graze, it’s harder to prove that the presence of animals won’t do damage to the trees, soil, and forages. Certainly there are plenty of examples of cows overrunning saplings, goats and sheep stripping tree bark, and pigs rooting deep holes around tree roots. And in some circumstances these behaviors can be used as a tool, while in other situations they need to be avoided, because they can inflict serious harm on the landscape.

In any given area of land, there is only a finite amount of food. The type of animal dictates the amount of food that can be utilized. The role of the farmer, then, is to assess the available food in a paddock, and ensure that animals are removed not only before that supply is diminished, but also before it is degraded so much that it cannot recover in a reasonable period of time.

Pigs grazing a woodland at Joel Salatin’s Polyface Farm. Grazing a paddock means ensuring that an animal has enough food, and supplementing if not, as noted here by the grain feeder in back. Once animals run out of food, damage is being done as they look for more. Photo by Jessica Reeder/ Wikimedia.

Overgrazing is overgrazing. This isn’t a question of how much the land can take, but of managing things in a way to ensure there is no harm done to the landscape. Overgrazing is simply giving animals access to a parcel of land for too long, which depletes both the existing vegetative resource and potentially the soil resource, too. Overgrazing also means that the recovery of the grazing area is very slow, or impossible.

In silvopasture, this is further complicated by the fact that trees don’t display signs of stress or decline as immediately as other plants do. While the evidence of damage to grasses and forages often appears in one season or less, trees may not exhibit the consequences of poor management until 5 or 10 years down the line.

All animals can overgraze, but there are additional challenges with larger animals (cows and pigs) and their potential impact due to soil compaction and damage to both surface roots and trees; there is even further concern with pigs rooting and destroying soil structure completely. Responsible farmers need to recognize this real threat and act accordingly. Management must be active and continual, and assumptions about the potential impacts need to be questioned continually.

Rather than attempt to define any absolute terms to say if one practice is right and another wrong, it’s more important to keep the following questions in the forefront of your mind as you design and implement silvopasture:

- Is there bare ground as a result of grazing or foraging activity?

- Is there a loss or decline of forage quantity and density as a result of grazing?

- Has the percentage of organic matter increased, or decreased, over time?

- Is the soil more or less compacted over time?

- Is there any evidence of abnormal decline in the trees?

A key factor in answering these questions comes back to animal behavior, which is discussed in more detail starting on page 70. Animals that have access to ample food and are removed from an area before food becomes scarce and they become bored are less likely to do damage to plants, soil, and trees. A basic indicator we can name is: Bare soil equals degradation. But this alone isn’t sufficient, because bare ground means you’ve gone far beyond the threshold, and any remedial action will be too little, too late.

Timing is of the essence, and in all cases with all types of animals, it’s better to err on the side of too soon, rather than too late. A farmer’s flexibility with this relates directly to the amount of available pastureland. All too often farmers push this capacity to the maximum, rather than allowing themselves ample room to be flexible and adaptable.

In practice this means always being ahead of the game, having the infrastructure in place so that animals can move when they need to. At our farm we have learned over time to have enough fencing on hand to build two to three paddocks at a time, which allows us to move the sheep when they should move, not when we can scrape together the time in our busy schedules.

Assumptions are what get us all in the end—assuming that no damage is being done from overgrazing, for instance, or that the season will have optimal rainfall, temperature, and weather. The best farmers expected the unexpected and already have a Plan B in their pocket to fall back on.

On the flip side, one of the wonderful things about pasturing animals is the potential to always improve the on-site food source in both quantity and quality. This is the big advantage of utilizing farming systems with grazing ruminants (sheep, goats, cows), who can digest forages as the majority or entirety of their diet, versus grain-fed animals like pigs and poultry, which benefit only marginally from pasture improvement in comparison. Because of this factor, you will note that this book favors promoting the use of ruminants in silvopasture over monogastric (single-stomach) animals, though the options for regenerative use of several common species will be considered.

Key Silvopasture Points

- Start integrating silvopasture with the most marginal parts of the land.

- Work with what you’ve got; invest in improvements later.

- Start small and build slowly. Don’t have too much diversity.

- Take a lot of time selecting the animal and breed, and know you might need to train them.

- Start with animals well under the stocking rate.

- Honor the animals’ body wisdom.

- Ruminants are most silvopasture-ready.

- Poultry are low-risk and low-impact.

- Exercise extreme caution with pigs.

- Accept and plan for tree mortality.

- Value the shade, shelter, and fodder functions of trees.

- Keep some pasture as pasture, some woods as woods.

- Plan on mowing, pruning, cutting, and more for several years.

- Remember that what we know is less than what we don’t.

Recommended Reads

Low-Risk Silvopasture: Chickens, Turkeys, Guinea Hens, Ducks and Geese

Recent Articles

“An immediate halt to chemical fertilizing and returning to the use of compost instead would turn degeneration into regeneration.”

Read MoreIf you’re not familiar with silvopasture, you should be. The integrated system offers both the promise of land regeneration and economic livelihood.

Read MoreAs the weather heats up, now’s the perfect time to grow and pick cucumbers! With these easy tips and tricks, you’ll be prepared to successfully harvest and store the cucumbers you grow until they’re ready to eat. Unless otherwise noted, all photographs copyright © 2017 by Andrew Mefferd. The following is an excerpt from The Greenhouse and…

Read MoreSome of the world’s most productive and resilient soils contain significant quantities of “natural” biochar. Author Kelpie Wilson challenges us to “change our perspective from ‘too much carbon in the air’ to ‘not enough carbon in the soil.’ We are good at being miners and exploiting resources, so let’s mine the air and stash the…

Read MoreAside from the sheer pleasure of telling your friends, straight-faced, that you maintain your garden using something called a “chicken tractor,” there are a slew of other benefits to working the land with a few of your animal friends. Getting rid of pests without chemicals, for one; letting them do the work of weeding and…

Read More