Become A Plant Breeder: The Seed Series

It’s time to take control of your seeds and become a plant breeder! Saving your seed allows you to grow and best traditional & regional varieties, and develop more of your own.

The following excerpt is from Breed Your Own Vegetable Varieties by Carol Deppe. It has been adapted for the web.

Becoming A Plant Breeder

Developing new vegetables doesn’t require a specialized education, a lot of land, or even a lot of time. It can be done on any scale. It’s enjoyable. It’s deeply rewarding. You can get useful new varieties much faster than you might suppose. And you can eat your mistakes.

Gardeners buy only small amounts of seed compared to commercial growers, so seed varieties that are best suited for gardeners are only sold in small amounts. Large seed companies often can’t afford to carry it. No one can make a profit developing it. So no one is.

If we gardeners want good new garden varieties, we’ll have to breed them ourselves.

But this is as it should be. Gardeners have been developing their own varieties for centuries. Besides, why should we let the professionals have all the fun?

Why Save Seeds?

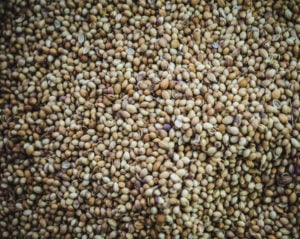

Saving seeds is fun. Cleaning the seed, holding the clean seed in your hands, is magical.

Gaze at the seed, run your fingers through it, play with it, and you can feel the connections. You’re like a child with a gallon bucket of marbles, or a squirrel sitting on a hollow log full of acorns.

Unquenchable joy arises. It is so intense it puzzles you initially. Then you recognize it. It is the joy that comes from being who you are supposed to be and doing what you are meant to do.

Seed saving is practical. If you know how to save your own seeds you can grow rare varieties.

Many of the most spectacularly flavorful, unique varieties are not readily available commercially, either as fruits or seed.

One of my favorite winter squash is ‘Blue Banana’, for example. This squash has a flavor that is superb, intense, and so different from all other squash that it is like an entirely different vegetable. But the seed is not available commercially.

Becoming A Plant Breeder: Growing Rare Varieties

To grow rare varieties, you often have to get the seed when and where it is available, then maintain the variety yourself.

Some varieties are not available because they have peculiarities with respect to production of the seed itself. If a watermelon produces few seeds, for example, it will not usually be offered commercially. It’s simply too expensive to produce the seed.

A home gardener, though, might be happy to save such seed. And a market garden might be able to easily produce the handful of seeds needed for a single field’s planting.

Being dependent upon seed companies for your seed means being dependent upon random fads in foods as well as other people’s choices and preferences. Saving your own seed means independence. It lets you make your own choices and have your own preferences.

The Convenience of Saving Seeds

When you save your own seed, the seed is always “available.” It is common these days for all the seed of even very popular varieties to be produced by just a single grower. If that grower experiences a crop failure, the seed isn’t available anywhere.

Sometimes, even if the seed is “available,” you can’t necessarily find it. There can be a poor correlation between variety names and the material you actually receive. Seed companies often change lines or suppliers, so that what they are selling one year and the next may be different strains, even though they are called the same thing.

I like to produce my own seed even of varieties that are readily available commercially. My own seed is usually bigger, fatter, and more vigorous. I can plant it earlier than commercial seed. I also have much more of it, so I don’t have to skimp.

I can sow generously and then thin, instead of sowing thinly, then having gaps that have to be replanted later and less optimally. And with my own seed, the price is right.

How to Become A Plant Breeder

When you save seed, you become a plant breeder. You are choosing which germplasm to perpetuate. This means that you are both deliberately as well as automatically selecting for characteristics that are important to you, for plants that are fine-tuned to your needs and growing conditions and region.

After you have saved seed of a variety for a few years, you have your own line of the variety that is slightly different from anyone else’s, and it is usually better adapted to your needs.

Knowing how to save your own seed also means that you can take advantage of genetic accidents, ideas, and dreams. Last year, for example, I noticed one squash plant in perhaps a hundred that was resistant to powdery mildew. I saved the seed from it.

Perhaps I can use it to develop new powdery-mildew-resistant varieties. Powdery mildew after the first fall rains is what ends the squash growing season in my region. Resistant varieties could be very useful. Many new varieties got their start when some gardener or farmer simply noticed something that was different and special-and saved the seeds.

We gardeners and farmers care about our direct relationship with soil, plants, and food. To grow plants from seed bought from others is one level of relationship. To grow plants from our own seed, to save seeds from our own plants, goes to a deeper level.

It is fulfillment and continuity-plants and people maintaining each other, nurturing each other, evolving together. It completes the circle.

Saving Seed from Hybrids

Hybrids don’t breed true to type from seed.

Some hybrids are even sterile, though most will produce seed. This seed can be used to derive a pure-breeding variety by the methods described in chapters 9 and 10.

Such a variety derived from a hybrid is a new variety and should be given a new name.

It is not the same as the hybrid from which it was derived.

In other words, you can save seed from hybrids as the first step in creating a new open-pollinated variety, but you cannot reproduce a hybrid by saving its seed.

This section on seed-saving practice, then, refers to pure-breeding, not hybrid, varieties.

Seed-Saving Overview

Saving seed is easy. Plants want to make seed. They cooperate fully. To save seed, all you have to do is let the plants produce seed, then grab it quick before the birds or squirrels or bugs, and before it gets rained on and molds or sprouts in the pod.

Saving seed of pure varieties is another thing entirely. Plants don’t care at all about pure varieties.

The outbreeders would all rather cross with that strange inedible ornamental variety down the street in the yard of your neighbor. Even the inbreeders outcross far more often than they are “supposed to”, especially under organic growing conditions.

To save seed of pure varieties, we need to know something about the outcrossing tendencies of the crop so that we can isolate it sufficiently from other varieties or wild plants of the species that it could cross with.

Genetic Variability

Finally, every variety contains genetic variability. Some of this is desirable and even essential to the vigor and adaptability of the variety.

Some of it, though, is undesirable. So, we need to grow an appropriate number of plants in order to maintain the amount of genetic variability that we want. At the same time, we must select and rogue to eliminate the genes associated with specific kinds of variability that we don’t want.

Given the genetic heterogeneity in most varieties and the greater vigor of the more wild-type forms, the natural tendency of most varieties is to deteriorate quickly to something that is far less useful to its human associates. To maintain a variety we must actively breed in order to counter this tendency.

There is actually no such thing as “saving” a pure variety. There is only further breeding, either deliberate or accidental.

We either select in order to hold the variety in its current form and to eliminate undesirable types, or we select in order to change the variety in some preferred direction.

Both processes involve exactly the same principles.

Roles and Purposes

“What’s my role with respect to this variety?” That’s the first thing I ask myself about every seed-saving project.

Am I the sole savior or creator of the variety, the one person without whom it would be lost forever? Or is my line better than everyone else’s, and especially worthy of preserving and distributing?

Am I planning on building up the precious stock, then giving or selling it to seed companies or others? Will I be distributing it through the Seed Savers Exchange?

Will many or even all future plantings of this variety all over the country be descendants of these seeds I hold in my hands today?

If so, I will want to be pretty careful and rigorous. I will use serious numbers of plants, and serious isolation distances.

Saving Seed for Yourself

Often, however, I’m saving seed just for myself, and I know others have the variety as well. In that case, I can be quite casual about most nearly everything. Numbers of plants? I grow what I need for the table, and use special tricks to deal with maintaining heterogeneity.

Isolation? It’s often minimal. I usually plant so as to be able to recognize hybrids, which is much easier than avoiding them.

If I can recognize hybrids I can eliminate them or not as I choose in future generations. Who knows? The hybrid might be more interesting than the original material. And if the seed is just for my own use, what’s an outcross or two among friends?

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

“An immediate halt to chemical fertilizing and returning to the use of compost instead would turn degeneration into regeneration.”

Read MoreIf you’re not familiar with silvopasture, you should be. The integrated system offers both the promise of land regeneration and economic livelihood.

Read MoreAs the weather heats up, now’s the perfect time to grow and pick cucumbers! With these easy tips and tricks, you’ll be prepared to successfully harvest and store the cucumbers you grow until they’re ready to eat. Unless otherwise noted, all photographs copyright © 2017 by Andrew Mefferd. The following is an excerpt from The Greenhouse and…

Read MoreSome of the world’s most productive and resilient soils contain significant quantities of “natural” biochar. Author Kelpie Wilson challenges us to “change our perspective from ‘too much carbon in the air’ to ‘not enough carbon in the soil.’ We are good at being miners and exploiting resources, so let’s mine the air and stash the…

Read MoreAside from the sheer pleasure of telling your friends, straight-faced, that you maintain your garden using something called a “chicken tractor,” there are a slew of other benefits to working the land with a few of your animal friends. Getting rid of pests without chemicals, for one; letting them do the work of weeding and…

Read More